“One of the ways people inevitably increase their awareness when learning about other cultures is to move from thinking ‘My way is the only way’ toward thinking ‘There are many valid ways’ of interpreting and participating in life. And the process involves more than changing your thinking; it also involves adjusting your behaviors.”

Brooks Peterson, Cultural Intelligence (emphasis mine)

“The essence of ethnorelativism is respect for the integrity of cultures, including one’s own. In acceptance, the framework for appreciating cultural difference was established. At this stage, adaptation, skills for relating to and communicating with people of other cultures are enhanced.”

Milton Bennett, Towards Ethnorelativism (emphasis mine)

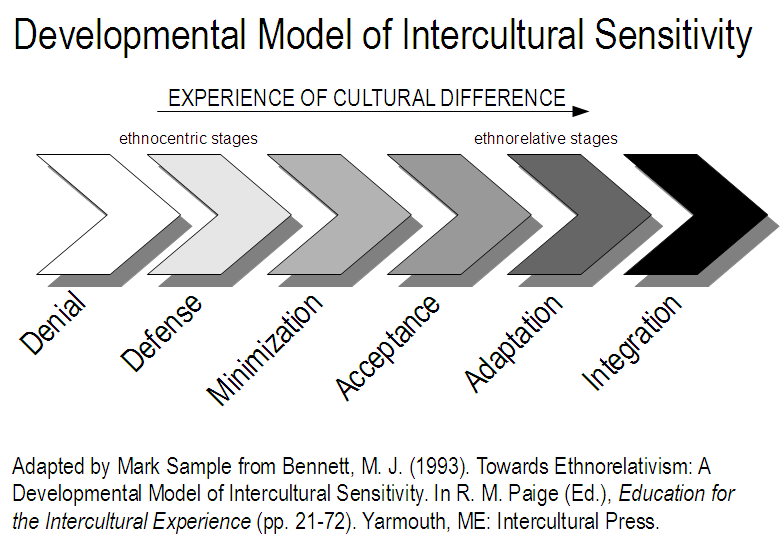

As we spend more time living and interacting with people in another cultural context, we may experience growth from Acceptance into Bennett’s next phase of intercultural sensitivity, Adaptation.

Acceptance (the previous phase) may have to do mainly with a change in perspective and attitude toward cultural difference (seeing it more positively, realizing it is there, being curious about and respectful toward difference), with an initial behavioral dimension of taking action to discover, understand, and learn about difference. It is possible to grow in accepting cultural difference, without living deeply or constantly in the midst of difference.

To grow into the phase of Adaptation, though, we need to be living in the context of cultural difference, and developing the skills for effective adjustment. This adjustment is comprehensive, involving cognitive, affective, and behavioral change over time. Cognitively, one begins to understand and see the world from the perspective of the people in the other culture. Behaviorally, one learns to adapt to do things in a way that is appropriate in the other setting. Affectively, one’s emotions are impacted over time, as feelings associated with the new worldview and cultural practices, and the value judgments associated with them, are internalized.

For example, through our years in Tunisia, we learned how Tunisians do hospitality. When someone you know shows up at your door, you don’t stand and talk with them at the door (unless you are male and the visitor is female, or vice versa, and no one of the other gender is at home with you), but welcome the visitor in (to stand and talk in the doorway implies you don’t want the visitor in your home). You must serve something, at least something to drink, and probably at least some kind of snack, if not a meal. You do not ask, “would you like…?” because such a request will be politely refused. Rather, you simply bring out the drink(s) and food, and serve them up. If you are eating a meal, you insist your visitor join you. If it is near a meal time, you plan on the visitor staying and eating with you (and insist that they do). In the Tunisian setting, rather than “a man’s home is his castle,” the guiding motto is, “my home is your home.” Rather than the honored one being the guest being received, in Tunisia, it is the host who is honored by the visit (hosts will say to visitors, “we have been visited by blessing”). A different way of viewing the world, people, social interactions, hospitality…

After living for years in Tunisia, and adapting to the Tunisian way of doing hospitality, we were often (emotionally) uncomfortable in hospitality situations in the U.S. For example, we were at my family’s eating one evening, and a couple of visitors dropped by unexpectedly. They were invited in (they were a sister-in-law and her friend; if they had been less close, perhaps they would not have been invited in), but we sat and continued eating, while talking with them. No one even offered for them to join us. (The expectation, in the U.S. setting, was that they had “interrupted” us in our plan or schedule, and would not have expected plans to be adjusted for them.) The fact that we felt uncomfortable shows that we experience adaptation even at the affective level, over time.

Note that adaptation, in Bennett’s model, is not assimilation. You don’t give up your culture, but experience an extension of your cultural repertoire.

“In adaptation, new skills appropriate to a different worldview are acquired in an additive process. Maintenance of one’s original worldview is encouraged, so the adaptations necessary for effective communication in other cultures extend, rather than replace, one’s native skills. The key to this additive principle is the assumption that culture is a process, not a thing. One does not have culture; one engages in it.”

One of the key skills in Adaptation is the ability to “look through the others’ eyes,” to construct reality that is nearer to their reality. Bennett contrasts this “empathy,” with the “sympathy” of ethnocentrism.

|

Can we adapt to the different other? |

“…I have contrasted empathy to ‘sympathy,’ where one attempts to understand another by imagining how one would feel in another’s position. Sympathy is ethnocentric in that its practice demands only a shift in assumed circumstance (position), not a shift in the frame of reference one brings to that circumstance; it is based on an assumption of similarity, implying other people will feel similar to one in similar circumstances. Empathy, by contrast, describes an attempt to understand by imagining or comprehending the other’s perspective. Empathy is ethnorelative in that it demands a shift in frame of reference; it is based on an assumption of difference, and implies respect for that difference and a readiness to give up temporarily one’s own worldview in order to imaginatively participate in the other’s.”

Adaptation takes time. And it changes us. As we live in another cultural setting, and adapt to the behavior, worldview, and even the value judgments and emotions accompanying sociocultural experience, we change. Even though this is not a process of assimilation, of exchanging our culture for the other, we become different people through the process. One author has called such people, “150% people.” And Bennett talks of becoming “marginal,” in the sense of becoming a person who is not straightforwardly “at home” in any cultural setting. When I returned to Minnesota after years in Tunisia (which used to be “home” but now no longer seems to be – for us know, “home” is wherever we are living), I could recognize my native culture, but I felt as if I was seeing it through different eyes. And indeed, I was. I had not become Tunisian, but I was no longer Minnesotan in the way I had been.

Would the cause of peace in the world be furthered, if more people entered into the world of different others, learning to deeply empathize, learning to see as they see, learning to understand how their behavior makes sense in its context, experiencing the fullness and richness of their life in all its dimensions? It seems that it would at least be a step in the right direction…

For more detail, see

Bennett, Milton J., “Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.” In Paige, R.M. (Ed). (1993) Education for the Intercultural Experience (2nd ed., p. 21-71). Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Bennett, Milton J., “Becoming Interculturally Competent.” In Wurzel, Jaime S., ed., Toward multiculturalism: A reader in multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 62-77). Newton, MA: Intercultural Resource Corporation, 2004.