Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Saturday, August 20, 2011

Israelis speak about the urgency of reaching a two-state solution

Here are a number of Israelis, on the J Street website, advocating a two-state solution.

I'm not sure whether a two-state solution is possible or desirable. Is anyone considering the possibility of changing the program for a "Jewish" state (given, for example, the conflict between being "Jewish," on the one hand, and being "democratic" on the other), and going for a one-state solution, with full equal rights for all citizens, Jewish and Arab, Jew, Muslim and Christian?

I'm not sure whether a two-state solution is possible or desirable. Is anyone considering the possibility of changing the program for a "Jewish" state (given, for example, the conflict between being "Jewish," on the one hand, and being "democratic" on the other), and going for a one-state solution, with full equal rights for all citizens, Jewish and Arab, Jew, Muslim and Christian?

Friday, August 19, 2011

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Peace Post of the Day: "Christian Terrorism in Norway?"

Check out this excellent article by Joseph Cumming, Director of the Reconciliation Program of the Center for Faith and Culture at the Yale Divinity School. He reflects on the recent "Christian" terrorist attack in Norway, and concludes, "Thus, Christians have a terrorism problem too. It flows from the kind of tribal thinking that is a catastrophic misinterpretation of the Christian faith, but it is a misinterpretation that this killer is not alone in believing. And if we search our consciences honestly, some of us may find just a little bit of that misinterpretation hidden in our own hearts."

Tribalism works against peace, whatever people and religious context it takes root in.

Tribalism works against peace, whatever people and religious context it takes root in.

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - different gods, more likely to fight?

“...the more different the gods worshipped by various peoples, the more likely, all other things being equal, that their respective worshippers will come into conflict and the less likely that they will find peaceful resolution of conflict”

“The claim that Muslims and Christians worship radically different deities is good for fighting, but not for living together peacefully.”

Miroslav Volf, Allah: A Christian Response

I'm not sure.

Volf's book is excellent, and I agree with most of his arguments and his main points. I'm not sure, though, that I agree that there is a correlation between how different peoples' conceptions of God are, and their likelihood of experiencing conflict.

Some thoughts:

1. I wonder if closeness in concept of God may be even more of an irritant, at least in some cases. Take (at least in certain times and places) different groups of Christians, e.g., Catholic and Protestant. We're talking about the same God, or at least a fairly close conception, and yet, plenty of conflict.

2. It seems to me more significant, whether a group's concept of God is one that tends toward peace and forgiveness and peacemaking or not. E.g., Jesus teaches us to forgive, to make peace, to love our neighbors and even our enemies. Regardless of whether Muslims or anyone has a close conception of God to mine, as a follower of Jesus, I should - if I follow the teachings of Jesus - do everything possible to live in peace with those others.

On the second quote, I think that the correlation is that in times of tension (like those between Muslims and Christians, post-9/11), both communities are more likely to emphasize different concepts of God, in a knee-jerk reaction to push away those different others that they are in conflict with. One could also say (reinforcing my point #2) that the view of God of the extreme Muslims, is a violent view, and leads them to their violent actions. But their view is considered by the vast majority of Muslims to be extreme and not representative of the true teachings of Islam.

In any case, I recommend Volf's book as a good and critically important read in these days of Muslim-Christian tensions.

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

Working for Peace in Palestine: Lynne Hybels

"So . . . it was October 2008. I had been invited by Dr. Gilbert Bilezikian—Bill’s mentor and mine—to attend a conference in Amman, Jordan, taught entirely by Arab Christians from Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq and the West Bank. To a person, these ministry leaders said they felt abandoned by Western Christians. And, of course, they are; to most Western Christians the phrase “Arab Christian” is an oxymoron. We experience a severe case of cognitive dissonance when hear about indigenous Iraqi Christians or the ancient Egyptian Coptic Church or—even more surprising—Palestinian Christians whose ancestors have been “on the land” from the time of Christ. What? Why didn’t we realize this? What should we do about it?"

So began the journey of Lynne Hybels - wife of the lead Pastor of one of America's first and largest megachurches - into the world of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Her posts and activities are worth following.

So began the journey of Lynne Hybels - wife of the lead Pastor of one of America's first and largest megachurches - into the world of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Her posts and activities are worth following.

Labels:

Lynne Hybels,

Palestinian-Israeli conflict

Can Evangelicals be a Force for Peace in Israel/Palestine?

"The World Evangelical Alliance Peace and Reconciliation Initiative (WEAPRI) has been established in order to respond to the extraordinary opportunity that 600 million evangelicals have, to reach out to the world as Peace-makers through the Church and Christian community internationally. With its secretariat in Auckland, New Zealand and its governance maintained by an International Executive Committee of experienced practioners, WEAPRI was formally inaugurated in October 2008."

This sounds good, but I wonder: can evangelicals be a force for peace - rather than for further destruction - in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict? The blind support offered by many evangelicals for the State of Israel has been a negative rather than a positive force in the region, from a perspective of peace, justice, human rights and international law. Will the WEAPRI be any different?

This sounds good, but I wonder: can evangelicals be a force for peace - rather than for further destruction - in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict? The blind support offered by many evangelicals for the State of Israel has been a negative rather than a positive force in the region, from a perspective of peace, justice, human rights and international law. Will the WEAPRI be any different?

Labels:

evangelicals and Israel,

Palestine,

WEAPRI

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Voice for Peace - Sami Awad interview

Labels:

Christians and Muslims,

Holy Land Trust,

Palestine,

Sami Awad

Sunday, July 24, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - taking Jesus seriously: proving love of God by loving enemies

“The biblical test case for love of God is love of neighbor. The biblical test case for love of neighbor is love of enemy. Failure to love the enemy is failure to love God.”

- Wayne Northey, in the book Unconditional? The Call of Jesus to Radical Forgiveness, by Brian Zahnd

It seems fairly obvious that if people (starting with Christians) were to take Jesus' teaching seriously, and to "prove" their love of God by loving their neighbors and loving even their enemies, the impact for peace in this world would be incalculable.

- Wayne Northey, in the book Unconditional? The Call of Jesus to Radical Forgiveness, by Brian Zahnd

It seems fairly obvious that if people (starting with Christians) were to take Jesus' teaching seriously, and to "prove" their love of God by loving their neighbors and loving even their enemies, the impact for peace in this world would be incalculable.

Labels:

Brian Zahnd,

Jesus,

love of enemy,

love of neighbor,

Wayne Northey

Saturday, July 23, 2011

Peace Blogs of the Day - The Warmonger's Fruit of the Spirit and The Warmonger's Lexicon

Check out two posts critiquing American Christian support of war:

The Warmonger’s Fruit of the Spirit, which begins:

"It seems sensible and logical that followers of someone called the Prince of Peace would not act like they are following Mars, the Roman god of war.

It seems to me that the cause of peace (and the prophetic role and witness of Christians) is harmed by the politicization/ideologization of faith in the American context - i.e., Christians aligning themselves with one political party or ideology (mainly, conservative Republican) or another.

As the author of the above blog posts notes, it is ironic and worse, that those calling themselves "Christians," i.e., followers of Jesus, the "Prince of Peace" and the one who said "blessed are the peacemakers," should be so strongly in support of the U.S. war machine.

Christians in America need to take another look at Biblical values, and what it means to stand for the teachings of Jesus. We need to get away from party politics, and away from knee-jerk support of American war efforts, and back to a role of critiquing the actions of our government from the perspective of Biblical values, across the board.

The world needs Christians to be a force for peace, not for war.

The Warmonger’s Fruit of the Spirit, which begins:

"It seems sensible and logical that followers of someone called the Prince of Peace would not act like they are following Mars, the Roman god of war.

As I have maintained whenever I speak about Christianity and war, if there is any group of people that should be opposed to war, empire, militarism, the warfare state, an imperial presidency, blind nationalism, government war propaganda, and an aggressive foreign policy it is Christians, and especially conservative, evangelical, and fundamentalist Christians who claim to strictly follow the dictates of Scripture and worship the Prince of Peace."

and The Warmonger’s Lexicon, which begins:

"Defenders of U.S. wars and military interventions look like the majority of Americans. They also dress like them, eat like them, work like them, play like them, and talk like them. However, it is sometimes impossible to communicate with or make sense of them because some things they say have their own peculiar definition.

This differs from military doublespeak.

To really understand these defenders of U.S. wars and military interventions, one needs a warmonger's lexicon. To get started, I propose the following entries:

Just war: any war the United States engages in.

Good war: any war in which the United States is on the winning side.

Defensive war: any war the United States starts."

Good war: any war in which the United States is on the winning side.

Defensive war: any war the United States starts."

As the author of the above blog posts notes, it is ironic and worse, that those calling themselves "Christians," i.e., followers of Jesus, the "Prince of Peace" and the one who said "blessed are the peacemakers," should be so strongly in support of the U.S. war machine.

Christians in America need to take another look at Biblical values, and what it means to stand for the teachings of Jesus. We need to get away from party politics, and away from knee-jerk support of American war efforts, and back to a role of critiquing the actions of our government from the perspective of Biblical values, across the board.

The world needs Christians to be a force for peace, not for war.

Labels:

Christians and war,

warmonger

Sunday, July 17, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - are Christian Zionists contributing to peace?

God save us from these people [Christian Zionists]. When you see what these people are encouraging Israel and the U.S. Administration to do – that is, ignore the Palestinians, if not worse, if not kick them out, expand the settlements to the greatest extent possible – they are leading us into a scenario of out-and-out disaster.

Yossi Alpher (60 Minutes, “Zion's Christian Soldiers,” Oct. 6, 2002)

quoted in David Brog, Standing With Israel: Why Christians Support the Jewish State

Monday, July 11, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - We must interfere (Elie Wiesel, Night)

I remember: it happened yesterday, or eternities ago. A young Jewish boy discovered the Kingdom of Night. I remember his bewilderment, I remember his anguish. It all happened so fast. The ghetto. The deportation. The sealed cattle car. The fiery altar upon which the history of our people and the future of mankind were meant to be sacrificed.

I remember he asked his father, 'Can this be true? This is the twentieth century, not the Middle Ages. Who would allow such crimes to be committed? How could the world remain silent?'

And now the boy is turning to me, 'Tell me,' he asks, 'what have you done with my future , what have you done with your life/' And I tell him that I have tried. That I have tried to keep memory alive, that I have tried to fight those who would forget. Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.

And then I explain to him how naïve we were, that the world did know and remained silent. And that is why I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men and women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must – at that moment – become the center of the universe.

Elie Wiesel, Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech, recorded in Night

Everyone should read Night. Wiesel is right, we must remember (the horrors of the Nazi Holocaust). And Wiesel is right – our moral obligation, to God and to humanity, is to know human suffering – all human suffering, everywhere, by and of any people – and to take action on behalf of the victims. And that includes the Palestinians.

Labels:

Elie Wiesel,

Night,

The Holocaust

Friday, July 1, 2011

Book for Peace - Allah: A Christian Response

I have read many books (and answered many questions) related to the question of whether Christians and Muslims worship the same God. This is the best book I have read on the subject, and it is particularly helpful and interesting because Volf addresses the broader context, including ways in which God and religion serve as identity markers and contribute to conflict between groups. His discussion of the views of some key historical figures (including Martin Luther) on the question is very helpful. And a significant part of the book is the discussion of whether Christians and Muslims can find a way to work together for the "common good" (rather than trying to destroy each other).

I highly recommend this book, for Christians and Muslims alike. But to benefit, you have to approach it with an open mind...

I highly recommend this book, for Christians and Muslims alike. But to benefit, you have to approach it with an open mind...

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Hope for Peace? Reflections by Rick Love on the "Building Hope" Conference

Monday, June 27, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - Christians & Muslims are Key to Peace

"Muslims and Christians together make up well over half of the world’s population. Without peace and justice between these two religious communities, there can be no meaningful peace in the world. The future of the world depends on peace between Muslims and Christians."

Sunday, June 26, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - Fighting Over God

"The claim that Muslims and Christians worship radically different deities is good for fighting, but not for living together peacefully."

Miroslav Volf, Allah: A Christian Response

Thursday, June 23, 2011

The Wars are Killing Us

Jim Wallis's article, "The War Must Not Go On," made me think of an issue that surfaced this past 10 days in the "Building Hope" Conference at the Yale Center for Faith & Culture, among Jews, Christians and Muslims.

More than one of the Muslims, who are very much in good relationship with Christians, and in favor of peaceful coexistence, said that when they talk with Muslims (especially in the Middle East and Asia), the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are "killing them." Muslims always ask them, "you say / we hear that Jesus taught peace and love, but where is the peace and love in Christian America waging war on Muslims in Iraq and Afghanistan?"

If you are American Christian, listen carefully: for most Muslims in the world, relationship with Christians is being undermined, I would say being destroyed, by the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Jim Wallis is right - the war must not go on.

For the sake of Muslim-Christian relations, which for Christians includes the sake of bearing positive witness to the "good news" of Jesus Christ, and for the sake of peace in the world, the wars must stop.

P.S. The other key issue, which makes it very hard for Muslims trying to present a "moderate" approach to Muslims around the world, and also for us as Americans (for me, as an American Christian), is the Israeli-Palestinian situation. Another war, which stirs up further animosity, hatred, strife, and more violence.

More than one of the Muslims, who are very much in good relationship with Christians, and in favor of peaceful coexistence, said that when they talk with Muslims (especially in the Middle East and Asia), the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are "killing them." Muslims always ask them, "you say / we hear that Jesus taught peace and love, but where is the peace and love in Christian America waging war on Muslims in Iraq and Afghanistan?"

If you are American Christian, listen carefully: for most Muslims in the world, relationship with Christians is being undermined, I would say being destroyed, by the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Jim Wallis is right - the war must not go on.

For the sake of Muslim-Christian relations, which for Christians includes the sake of bearing positive witness to the "good news" of Jesus Christ, and for the sake of peace in the world, the wars must stop.

P.S. The other key issue, which makes it very hard for Muslims trying to present a "moderate" approach to Muslims around the world, and also for us as Americans (for me, as an American Christian), is the Israeli-Palestinian situation. Another war, which stirs up further animosity, hatred, strife, and more violence.

Theology of Destruction or of Reconciliation?

Does our theology lead us towards destruction or reconciliation? Toward being "for" someone and "against" another, or being for all?

Salim Munayer is one of my peace heroes.

Salim Munayer is one of my peace heroes.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day: Daisy Khan on Extremists

Okay, here's a trip:

Visiting the Edmond J. Safra Synagogue in New York City, led by Rabbi Elie Abbadie, with a group of Muslims, Christians and Orthodox Jews, and hearing Daisy Khan speak.

Daisy Khan is the wife of Imam Faisal, who has been at the center of the Ground Zero mosque controversy.

She is interesting, engaging, real, and anything but threatening. That, she says, is because (according to her critics) she is practicing takia, i.e., concealing the truth - "faking us out," so that she (they) can "take over and impose Sharia on America" (basically, the same as the Moral Majority, I guess?).

The thing is, I believe her, and I'm willing to risk something on that belief. (I would add that, in 30 years of living among Muslims, I have never seen any teaching or practice that supports the accusation of takia. And I think I have some ability to judge character.

Anyway, here's a quote, among other things she said:

“we must not be held hostage by extremists.”

She was speaking of Terry Jones, but her words are equally relevant to Muslim and Jewish extremists.

If we can't distinguish between extremists and others, we are going to have a very hard time moving forward.

Peace Quote of the Day - Seeking the Common Good?

“If we are going to seek the common good, we must seek what is good for all of us – Muslims, Christians and Jews, together”

(Dr. Rick Love, Peace Catalyst International - http://www.peace-catalyst.net/)

This is the way to seek peace - to seek the common good, for all; and preferably, to do this by working together.

Why I am A Rabbi for Human Rights

Rabbi David Shneyer of the Am Kolel Jewish Renewal Community of Greater Washington tells us why he is a “Rabbi for Human Rights.” He asks how one could be a rabbi and not support human rights. Rabbi Shneyer believes that we need an organization that stands for justice and human rights for all people, especially within the Occupied Territories. He believes it is wrong for us, given our history and background, to oppress other peoples.

Thank God there are people like this working for peace.

Thank God there are people like this working for peace.

Seven Resolutions Against Prejudice, Hatred and Discrimination

Peace Quote of the Day - the Grand Mufti of Bosnia Weighs In

At the UN yesterday, as part of Yale's "Building Hope" conference, we heard various speakers. Here is a word from Dr. Mustapha Ceric, the Grand Mufti of Bosnia-Hertzegovina:

“there are no just wars – all wars are unjust in terms of human suffering and loss”

Not what you expect to hear from a Grand Mufti?

Labels:

Building Hope Conference,

just war,

Mustapha Ceric,

UN

Sunday, June 19, 2011

Be Careful What Kind of Walls You Build

We had a fascinating interaction today, at the "Building Hope" conference, on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Presenters were Rabbi Douglas Krantz, one of the founders of J Street (see http://jstreet.org/), and Sami Awad of Holy Land Trust (http://www.holylandtrust.org/) and the film "Little Town of Bethlehem" (http://littletownofbethlehem.org/), which we viewed tonight (see it if you haven't).

The group consists of Muslims from various countries, Orthodox Jews from the U.S., Israel and elsewhere, and Christians from various countries - so you can imagine that there are many different opinions and perspectives.

I didn't know what to expect, whether our newly forming relationships would hold up under the pressures of diving into such a charged issue. I was pleasantly surprised. We were able to engage in frank, honest, and respectful conversation. Many shared their stories, personal experiences, and perspectives, and asked some tough questions. It was moving, at many points (in a positive way). It was enriching. We remarked again and again, the importance of the human dimension - relationship, getting to know the other. It's harder to stereotype and to hate someone you know (if you know them in the right way).

Rabbi Krantz talked about the danger of building walls, physical walls and intellectual walls (and other kinds). He remarked that "an intellectual wall is harder to tear down than a real wall" (and may exist long after the physical walls have been removed). He exhorted us to be careful of how we see ourselves, and how we talk about ourselves, and to be careful what kind of walls we build. An excellent word, which in a way summarizes much of what this conference has been about.

The group consists of Muslims from various countries, Orthodox Jews from the U.S., Israel and elsewhere, and Christians from various countries - so you can imagine that there are many different opinions and perspectives.

I didn't know what to expect, whether our newly forming relationships would hold up under the pressures of diving into such a charged issue. I was pleasantly surprised. We were able to engage in frank, honest, and respectful conversation. Many shared their stories, personal experiences, and perspectives, and asked some tough questions. It was moving, at many points (in a positive way). It was enriching. We remarked again and again, the importance of the human dimension - relationship, getting to know the other. It's harder to stereotype and to hate someone you know (if you know them in the right way).

Rabbi Krantz talked about the danger of building walls, physical walls and intellectual walls (and other kinds). He remarked that "an intellectual wall is harder to tear down than a real wall" (and may exist long after the physical walls have been removed). He exhorted us to be careful of how we see ourselves, and how we talk about ourselves, and to be careful what kind of walls we build. An excellent word, which in a way summarizes much of what this conference has been about.

Words for Peace from Imam Dawood

Another "peace nugget" from the Building Hope Conference:

We must meet and know people, if we are to grow toward peace. This is true whether we're talking about Christian-Muslim-Jewish relations, about race relations, or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We have to step out of our comfort zone, leave our bubbles, and meet The Other.

“it's much harder to hate someone once you know them” (Imam Dawood)

We must meet and know people, if we are to grow toward peace. This is true whether we're talking about Christian-Muslim-Jewish relations, about race relations, or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We have to step out of our comfort zone, leave our bubbles, and meet The Other.

An Organization Working for Peace: Encounter

Seeking peace through bringing people together - check out the work of Encounter:

http://www.encounterprograms.org/

http://www.encounterprograms.org/

Labels:

Encounter

Words for Peace by Sami Awad (from the Building Hope Conference)

Words for peace, from a talk by Sami Awad at the Building Hope Conference (you can follow it on Twitter at #buildinghope):

“if you want peace, you work for peace, and you never stop, no matter what the other side does”

“if you want peace, you work for peace, and you never stop, no matter what the other side does”

“finding a solution to just benefit one group or another, is not peace”

“peace is what you give, not what you take”

“peace is not a strategic option” (i.e., our commitment needs to be deeper and stronger than "strategy")

Saturday, June 18, 2011

Does Peace Lie in the Texts, or in the Interpretation and Application?

One thing that has become clear to me, as we - committed Christians, Muslims and Jews - discuss our sacred texts about various issues (like love of neighbor, the poor, violence including terrorism, and others), at the Building Hope Conference, is that our problem does not lie in our sacred texts, but in the interpretation and application of those texts.

To put it very simply, you can interpret and apply the texts - in any of our traditions - in a way that leads to and supports good relations and peace with others, or the opposite.

To give one example, which I keep coming back to, it is one thing to have a text that says "love your neighbor as yourself"; it is another to decide what that means and who it applies to (Jesus threw a wrench in the works by applying the verse to the despised Samaritans, who the Jews of his day would never have thought of as their neighbors). And that's one of the "easy" or "nice" verses.

One of the things which encourages me about this conference is, the participants are deeply religious / committed, AND broad-minded, open-hearted, eager to live out their faith in good relations with those of other faiths (or none). That is encouraging.

We'll see how it goes tomorrow: we're talking about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. :-)

To put it very simply, you can interpret and apply the texts - in any of our traditions - in a way that leads to and supports good relations and peace with others, or the opposite.

To give one example, which I keep coming back to, it is one thing to have a text that says "love your neighbor as yourself"; it is another to decide what that means and who it applies to (Jesus threw a wrench in the works by applying the verse to the despised Samaritans, who the Jews of his day would never have thought of as their neighbors). And that's one of the "easy" or "nice" verses.

One of the things which encourages me about this conference is, the participants are deeply religious / committed, AND broad-minded, open-hearted, eager to live out their faith in good relations with those of other faiths (or none). That is encouraging.

We'll see how it goes tomorrow: we're talking about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. :-)

Peace Quote of the Day - how can we have peace, how can we "love our neighbor," if we don't "have" neighbors?

“My concern is not that we don't love our enemies, but that we don't love anyone; that we just love ourselves and those who it is convenient to love. … In the West, now, we are lacking even a sense of community, what it means to have literal, actual neighbors. … What would it look like for us to take our literal neighborhoods seriously?”

A Pastor Who is a Participant in the "Building Hope" Conference

Peace Quote of the Day - From "Enemy" to...?

“When we look deeply into our anger, we see that the person we call our enemy is also suffering. As soon as we see that, we have the capacity of accepting and having compassion for him. Jesus called this ‘loving your enemy.’ When we are able to love our enemy, he or she is no longer our enemy. The idea of ‘enemy’ vanishes and is replaced by the notion of someone suffering a great deal who needs our compassion. Loving others is sometimes easier than we might think, but we need to practice it.”

Thich Nhat Hanh, quoted in Johann Arnold, Seeking Peace

Labels:

Jesus,

Johann Arnold,

love of enemy,

seeking peace,

Thich Nhat Hanh

Friday, June 17, 2011

Is Israel Interested in Peace?

Labels:

Israel,

Jordan,

King Abdullah

Thursday, June 16, 2011

Love of Neighbor, Yes - But Who is Our Neighbor?

An interesting question came up yesterday, as we were talking about peacemaking and tolerance in our (Christian, Jewish and Muslim) traditions.

First of all, we all agreed that "tolerance" is a weak and insufficient goal. We want something more, and we need something more, if we are to be seeking and building peace with different others.

But then a question arose, as we considered what our sacred texts teach about our relationship with The Other.

A Jewish presenter shared the text,

The reason Adam was created alone in the world is to teach you that whoever destroys a single soul, Scripture imputes it to him as though he had destroyed the entire world; and whoever keeps alive a single soul, Scripture imputes it to him as though he had preserved the entire world.

But someone pointed out that there is another version,

FOR THIS REASON WAS MAN CREATED ALONE, TO TEACH THEE THAT WHOSOEVER DESTROYS A SINGLE SOUL OF ISRAEL,39 SCRIPTURE IMPUTES [GUILT] TO HIM AS THOUGH HE HAD DESTROYED A COMPLETE WORLD; AND WHOSOEVER PRESERVES A SINGLE SOUL OF ISRAEL, SCRIPTURE ASCRIBES [MERIT] TO HIM AS THOUGH HE HAD PRESERVED A COMPLETE WORLD.40

This raises the question, are Jews encouraged not to destroy / to save, Jewish life, or all life?

Similarly, a Muslim presenter shared the Hadith,

"None of you truly believes (in Allaah and in His religion) until he loves for his neighbor what he loves for himself,"

but another pointed out that this is "weak," that the "strong" version is

"None of you truly believes (in Allah and in His religion) until he loves for his brother what he loves for himself,"

with the understanding that "brother" means fellow Muslims.

And for Christians, does Jesus' teaching to "love your neighbor as yourself" mean fellow Christian, or all others? (Note, for example, that in Matthew 5:23-24 it says, "Therefore, if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there in front of the altar. First go and be reconciled to that person; then come and offer your gift." - does "brother or sister" mean fellow Christian, or everyone?)

I do not approach this from the position of arguing what Islam or Judaism teaches (e.g., some Christians argue that Islam teaches only love of Muslims). One question is what the texts say; another is, how do we interpret and apply them, what do we emphasize?

My perspective is that in any of our traditions we are faced with the question, how do we relate to people (The Other) outside our tradition, outside our community? What are our commitments? Are we committed to doing good to all people, loving all people, saving the life of all people? The potential is there, in each of our traditions, for inclusivity or exclusivity, for narrowness or breadth. And depending on the interpretation and the path we take, the end result can be conflict, oppression, even the extremes of ethnic cleansing and genocide.

As a Christian, I believe that our mandate, from Jesus, is to love all people. After all, when he taught that the second great commandment is to “love your neighbor as yourself,” the example he used to illustrate this (to his Jewish listeners) was the dispised, “half-breed,” “false religion” Samaritan. Every person is our neighbor. We are to treat every person as we ourselves want to be treated. There is no room, in the teachings of Jesus, for the kind of exclusive views that might lead us to devalue and ultimately dehumanize other people, whatever their gender or race or ethnicity or religion.

First of all, we all agreed that "tolerance" is a weak and insufficient goal. We want something more, and we need something more, if we are to be seeking and building peace with different others.

But then a question arose, as we considered what our sacred texts teach about our relationship with The Other.

A Jewish presenter shared the text,

The reason Adam was created alone in the world is to teach you that whoever destroys a single soul, Scripture imputes it to him as though he had destroyed the entire world; and whoever keeps alive a single soul, Scripture imputes it to him as though he had preserved the entire world.

But someone pointed out that there is another version,

FOR THIS REASON WAS MAN CREATED ALONE, TO TEACH THEE THAT WHOSOEVER DESTROYS A SINGLE SOUL OF ISRAEL,39 SCRIPTURE IMPUTES [GUILT] TO HIM AS THOUGH HE HAD DESTROYED A COMPLETE WORLD; AND WHOSOEVER PRESERVES A SINGLE SOUL OF ISRAEL, SCRIPTURE ASCRIBES [MERIT] TO HIM AS THOUGH HE HAD PRESERVED A COMPLETE WORLD.40

This raises the question, are Jews encouraged not to destroy / to save, Jewish life, or all life?

Similarly, a Muslim presenter shared the Hadith,

"None of you truly believes (in Allaah and in His religion) until he loves for his neighbor what he loves for himself,"

but another pointed out that this is "weak," that the "strong" version is

"None of you truly believes (in Allah and in His religion) until he loves for his brother what he loves for himself,"

with the understanding that "brother" means fellow Muslims.

And for Christians, does Jesus' teaching to "love your neighbor as yourself" mean fellow Christian, or all others? (Note, for example, that in Matthew 5:23-24 it says, "Therefore, if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there in front of the altar. First go and be reconciled to that person; then come and offer your gift." - does "brother or sister" mean fellow Christian, or everyone?)

I do not approach this from the position of arguing what Islam or Judaism teaches (e.g., some Christians argue that Islam teaches only love of Muslims). One question is what the texts say; another is, how do we interpret and apply them, what do we emphasize?

My perspective is that in any of our traditions we are faced with the question, how do we relate to people (The Other) outside our tradition, outside our community? What are our commitments? Are we committed to doing good to all people, loving all people, saving the life of all people? The potential is there, in each of our traditions, for inclusivity or exclusivity, for narrowness or breadth. And depending on the interpretation and the path we take, the end result can be conflict, oppression, even the extremes of ethnic cleansing and genocide.

As a Christian, I believe that our mandate, from Jesus, is to love all people. After all, when he taught that the second great commandment is to “love your neighbor as yourself,” the example he used to illustrate this (to his Jewish listeners) was the dispised, “half-breed,” “false religion” Samaritan. Every person is our neighbor. We are to treat every person as we ourselves want to be treated. There is no room, in the teachings of Jesus, for the kind of exclusive views that might lead us to devalue and ultimately dehumanize other people, whatever their gender or race or ethnicity or religion.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - what do the Talmud and Qur'an say about Murder?

The reason Adam was created alone in the world is to teach you that whoever destroys a single soul, Scripture imputes it to him as though he had destroyed the entire world; and whoever keeps alive a single soul, Scripture imputes it to him as though he had preserved the entire world. Babylonian Talmud

Because of this, we decreed for the Children of Israel that anyone who murders any person who had not committed murder or horrendous crimes, it shall be as if he murdered all the people. And anyone who spares a life, it shall be as if he spared the lives of all the people. Qur'an Surah 5:32

Because of this, we decreed for the Children of Israel that anyone who murders any person who had not committed murder or horrendous crimes, it shall be as if he murdered all the people. And anyone who spares a life, it shall be as if he spared the lives of all the people. Qur'an Surah 5:32

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Seeking Peace through "Building Hope"? Muslims, Christians and Jews at Yale

There is too much to reflect on coherently at this time, but a couple of thoughts about how to relate to the Other, in a way that might lead to something positive:

* We were encouraged last night that for deeper understanding, we must go beyond study of texts (history, etc.), and focus on developing friendship with others (the others we might be suspicious or afraid or ignorant of, in conflict with, etc.). In fact, that's why 30 of us - Muslims, Christians and Jews - are spending 10 days together, sharing life, sharing meals, sharing faith, and discussing difficult issues.

* We were also encouraged that the path to understanding usually leads through times of non-understanding. If we think we "understand" the Other from the start, what we really understand are just our own stereotypes of the Other, relating to an image rather than reality.

* Today, one of the Jewish speakers reminded us that Muslims and Christians both tend to think they understand Judaism, but what we really understand are our own versions of Judaism, based on our textual traditions. If we really want to understand Judaism (and Jews), we need to let them speak, and listen, to come to know them, and their version. The challenge, the speaker pointed out, is to hold our texts and images in one hand, and to create space for understanding Judaism on its own terms, at the same time.

What we experienced, today, was Muslims and Jews sharing about their beliefs and practices, and significant question and answer times (that were too short, but very significant); and lots of relational time, as well, over meals and breaks, interacting, getting to know each other, and - I hope - moving toward more of an understanding of Each Other as we really are (not as images).

This definitely seems like steps on the path toward peace. I'm hopeful...

Sunday, June 12, 2011

A "Salafi Pacifist" talking about Jihad, as a force for Peace?

Labels:

jihad,

salafi Muslim,

Yasir Qadhi

Peace Quote of the Day - Seeing the Light (a Rabbinic Perspective)

A rabbi asked his students: when, at dawn, can one tell the light from the darkness? One student replied: when I can tell a goat from a donkey. No, answered the rabbi. Another said: when I can tell a palm tree from a fig. No, answered the rabbi again. Well then, what is the answer? his students pressed him. Not until you look into the face of every man and every woman and see your brother and your sister, said the rabbi. Only then have you seen the light. All else is still darkness. (Hasidic tale)

Human nature being what it is, the ability to see a brother or sister in every person we meet is a grace. Even our relationships with those who are closest to us are clouded now and then, if only by petty grievances. True peace with others requires effort. Sometimes it demands the readiness to yield; at others, the willingness to be frank. Today we may need humility to remain silent; tomorrow, courage to confront or speak out. One thing remains constant, however: if we seek peace in our relationships, we must be willing to forgive over and over.

Johann Arnold, Seeking Peace

Labels:

Johann Arnold,

light,

seeking peace

Saturday, June 11, 2011

Friday, June 10, 2011

WWJD? A Nonviolent Conflict Resolution for Palestine (Sami Awad)

How could a person living under military occupation, experiencing first-hand suffering and humiliation, even think about loving the enemy, let alone urge family, friends and neighbors to do the same? This challenging message came from a young rabbi named Jesus in his “Sermon on the Mount.”

Of course, Jesus could have suggested we make peace with our enemies or negotiate peace agreements or peacefully resolve conflict; those statements would have been as shocking to the suffering Jews of that time. Instead, he entreated them to go further: to “love” them. This was the word he chose — a command to all those who seek to follow him...

Of course, Jesus could have suggested we make peace with our enemies or negotiate peace agreements or peacefully resolve conflict; those statements would have been as shocking to the suffering Jews of that time. Instead, he entreated them to go further: to “love” them. This was the word he chose — a command to all those who seek to follow him...

Thursday, June 9, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - the Torah and Human rights (a Jewish perspective)

"As rabbis, our first responsibility in [Rabbis for Human Rights] is to uphold the Jewish tradition of human rights. However, international law is a secular expression of that same love for humanity. International law was not created to be a gun pressed against our heads, but to learn from the darkest chapters of human history and serve as secular expression of the very Jewish belief in the intrinsic sanctity of every human being. ...

There would be no need for the Torah to teach us that every human being is created in God's Image were this obvious to us. It would not need to command us time and time again to love the stranger if this came easy to us. Were we to enjoy perpetual peace and harmony, neither the Torah nor international law would need to place limits on what is permissible in times of war. Were there no natural human desires to acquire as much as we can for personal gain, neither the Torah nor international law would need to insist that we worry about the needs of others or teach us about economic justice. The Jewish tradition would not need to put a curb on greed or remind us that "The earth belongs to Adonai," and that not everything in our bank account is really ours. ...

Our Jewish tradition and international law are necessary because our legitimate desires to find meaning and a sense of belonging through religious, national and ethnic in-groups can lead us down the slippery slope to human right violations perpetrated against out-groups. Our understandable desire to take control of our destiny and again enjoy national sovereignty as an answer to two thousand years of oppression, humiliation and wanderings can lead all to justifying our exclusive rights to theLand of Israel

God did not give us Torah out of a naïve belief that we live in an ideal messianic world in which it would be easy to observe the Torah, but out of a loving understanding of our human foibles. God knows that we are capable of evil, but as the psalm quoted above continues, "You have made humanity little less than the Divine" (Psalms 8:6) God did not impose the yoke of the commandments in order to oppress us, but out of a desire to inspire towards a better and more holy reality in which we will be the first to benefit. We are taught that the Torah is a Tree of Life. We are to live by the commandments, not die by them. The authors of international law were not naïve idealists sitting in a bubble. They loved and believed in humanity, but were scarred and painfully aware of the depths to which humanity can sink.

The Torah of human rights is not designed for some other fantasy world where they are not necessary. They are a loving gift to our imperfect, bleeding, shattered and screaming world, where they are desperately necessary."

There would be no need for the Torah to teach us that every human being is created in God's Image were this obvious to us. It would not need to command us time and time again to love the stranger if this came easy to us. Were we to enjoy perpetual peace and harmony, neither the Torah nor international law would need to place limits on what is permissible in times of war. Were there no natural human desires to acquire as much as we can for personal gain, neither the Torah nor international law would need to insist that we worry about the needs of others or teach us about economic justice. The Jewish tradition would not need to put a curb on greed or remind us that "The earth belongs to Adonai," and that not everything in our bank account is really ours. ...

Our Jewish tradition and international law are necessary because our legitimate desires to find meaning and a sense of belonging through religious, national and ethnic in-groups can lead us down the slippery slope to human right violations perpetrated against out-groups. Our understandable desire to take control of our destiny and again enjoy national sovereignty as an answer to two thousand years of oppression, humiliation and wanderings can lead all to justifying our exclusive rights to the

God did not give us Torah out of a naïve belief that we live in an ideal messianic world in which it would be easy to observe the Torah, but out of a loving understanding of our human foibles. God knows that we are capable of evil, but as the psalm quoted above continues, "You have made humanity little less than the Divine" (Psalms 8:6) God did not impose the yoke of the commandments in order to oppress us, but out of a desire to inspire towards a better and more holy reality in which we will be the first to benefit. We are taught that the Torah is a Tree of Life. We are to live by the commandments, not die by them. The authors of international law were not naïve idealists sitting in a bubble. They loved and believed in humanity, but were scarred and painfully aware of the depths to which humanity can sink.

The Torah of human rights is not designed for some other fantasy world where they are not necessary. They are a loving gift to our imperfect, bleeding, shattered and screaming world, where they are desperately necessary."

excerpt from an email from Rabbi Arik Ascherman, Rabbis for Human Rights

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - acknowledging the other

"What then is the source of our redemption, our salvation? It lies ultimately in our willingness to acknowledge the other - the victims we have created - Palestinian, Lebanese and also Jewish - and the injustice we have perpetrated as a grieving people. Perhaps then we can pursue a more just solution in which we seek to be ordinary rather than absolute, where we finally come to understand that our only hope is not to die peacefully in our homes as one Zionist official put it long ago but to live peacefully in those homes."

Sara Roy, quoted in Mark Braverman, Fatal Embrace

Labels:

Mark Braverman,

Sara Roy,

the other

Tuesday, June 7, 2011

Freedom for Palestine - music single

Labels:

music,

video clip

Monday, May 30, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - the Law of Retaliation or...?

"We are by nature a people who have the Law of Retaliation in our hearts: an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth (Ex. 21:24). But Jesus taught and lived a greater principle: 'I tell you, Do not resist an evil person. If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also' (Matt. 5:39). His first response was not to extract revenge, but to give the other person a chance. This is quite 'unnatural'; in fact, it is a work of God in someone's life to not retaliate against one who has wounded him or her."

Henry Cloud and John Townsend, How People Grow

Sunday, May 29, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - overcoming evil with evil is not making peace

"When we try to overcome evil with evil, we are not working for peace. If you say, ‘Saddam Hussein is evil. We have to prevent him from continuing to be evil,’ and if you then use the same means he has been using, you are exactly like him. Trying to overcome evil with evil is not the way to make peace."

Johann Arnold, Seeking Peace

Saturday, May 28, 2011

Website: If Americans Knew

Another website with a variety of information on the Palestinian-Israeli situation:

http://www.ifamericansknew.org/

Do you know? Does it make a difference?

http://www.ifamericansknew.org/

Do you know? Does it make a difference?

Thursday, May 26, 2011

The Killer: 'doodling, genocide, and experiences on the road'.

Here's a link to an excellent new interview with gametrekker Jordan Magnuson: 'I released a new notgame from Cambodia today'. The notgame, a powerful interaction with Cambodia's genocide, speaks for itself, and really deserves a play through (it takes about four minutes, and only requires holding down the space button, so no excuses about complexity or lack of time): The Killer. As one reviewer on Newgrounds states, 'This game [. . .] says more than all the news on TV'.

Asked in the interview why so many of his 'games' deal with such dark themes, Magnuson's response was a powerful reminder of why we need art in the first place -- to help us see the world truly, and remind us of all we have forgotten about each other, about pain, about life. To help us feel rightly, and encounter rightly:

Asked in the interview why so many of his 'games' deal with such dark themes, Magnuson's response was a powerful reminder of why we need art in the first place -- to help us see the world truly, and remind us of all we have forgotten about each other, about pain, about life. To help us feel rightly, and encounter rightly:

Yes a lot of my games and notgames deal with dark themes. Some of them deal with death, killing, genocide. I don’t think these are the only themes that games should be addressing, by any means, but I do think they are important themes that need to be addressed precisely because of the thoughtless and insensitive ways that games have addressed them in the past. When you think about it, nearly all of the games we make are already about death, already about killing, already about genocide.

But the expression of these things in our games has become so abstracted and dehumanized that we no longer recognize them for what they are. Death, as perceived through most of our computer games, loses almost all of the meaning it has had in the context of human lives and relationships throughout history. Thus, when it comes to the most significant themes in human experience, computer games have the tendency to strip meaning and significance out of those themes, strip empathy and understanding away from the people who play them.

I’m not saying I’m against RTS games, or chess, or even first person shooters. I’m just saying that for every game we have that makes life and death abstract to some extreme degree, I think we also need a game (or notgame) that solidifies them, humanizes them, reminds us of what we used to know about them.

Labels:

computer games,

Jordan Magnuson

Peace Quote of the Day - turning enemies into friends

“As long as we do not pray for our enemies, we continue to see only our own point of view – our own righteousness – and to ignore their perspective. Prayer breaks down the distinctions between us and them. To do violence to others, you must make them enemies. Prayer, on the other hand, makes enemies into friends. When we have brought our enemies into our hearts in prayer, it becomes difficult to maintain the hostility necessary for violence.”

Jim Wallis, quoted in Johann Arnold, Seeking Peace

Labels:

Johann Christoph Arnold,

prayer,

seeking peace

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

Peace Quote of the Day - our inability to be silent

"One of the greatest hindrances to peace is our inability to be silent."

"Mother Teresa points out that what we have to say is never as essential as what God says to us and through us: 'All our words are useless if they do not come from within. Words that do not carry the light of Christ only increase the darkness'."

"Mother Teresa points out that what we have to say is never as essential as what God says to us and through us: 'All our words are useless if they do not come from within. Words that do not carry the light of Christ only increase the darkness'."

Johann Arnold, Seeking Peace

Labels:

Johann Christoph Arnold

Monday, May 23, 2011

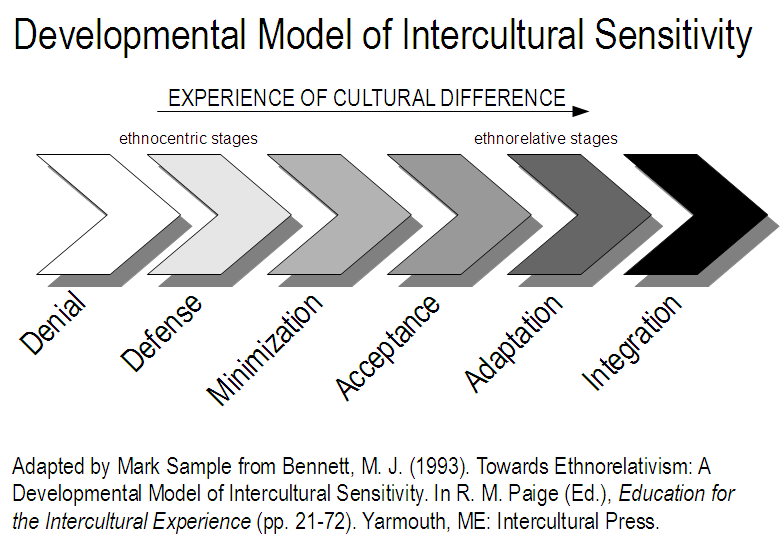

Beyond Ethnocentrism (3) – Pursuing Peace Through Growth in Intercultural Sensitivity: Integration

“A new type of person whose orientation and view of the world profoundly transcends his indigenous culture is developing from the complex of social, political, economic, and educational interactions of our time.”

Peter Adler, quoted in Bennett, “Towards Ethnorelativism”

(I wonder why he didn’t also say “religious” interactions? But that’s another subject…)

According to Adler, the “multicultural person” is one whose “essential identity is inclusive of life patterns different from his own and who has psychologically and socially come to grips with a multiplicity of realities” (quoted in Bennett).

Bennett refers to such as person as having developed to the ethnorelative stage of Integration.

At the stage of Integration, a person has come to be culturally marginal, existing on the periphery of two or more cultures. One is no longer straightforwardly at home in his or her original culture, neither has s/he assimilated to a different culture. The “integrated person” is not particularly affiliated with any one culture, but “can function in relationship to cultures while staying outside the constraints of any particular one” (all subsequent quotes, unless noted, are from Bennett).

People at the stage of Integration are living in the realm of what Bennett calls “contextual evaluation” – i.e., behavior is determined to be appropriate or not depending on the context (he asks the questions, “Is it good to take off my clothes?” and “is it good to refer directly to a mistake made by yourself or someone else?” and answers both by, “It depends on the circumstances” or context), and have the ability to choose from a range of different cultural responses, to given situations.

“These people see their identities as including many cultural options, any of which can be exercised in any context, by choice. They are not so much bound by what is right for a given culture (although they are aware of that) as they are committed to using good judgment in choosing the best treatment of a particular situation. … They are conscious of themselves as choosers of alternatives…”

Bennett points out that marginality “describes exactly the subjective experience of people who are struggling with the total integration of ethnorelativism.”

“They are outside all cultural frames of reference by virtue of their ability to consciously raise any assumptions to a metalevel (level of self-reference). In other words, there is no natural cultural identity for a marginal person. There are no unquestioned assumptions, no intrinsically absolute right behaviors, nor any necessary reference group.”

“They are outside all cultural frames of reference by virtue of their ability to consciously raise any assumptions to a metalevel (level of self-reference). In other words, there is no natural cultural identity for a marginal person. There are no unquestioned assumptions, no intrinsically absolute right behaviors, nor any necessary reference group.”For a personal example of what Bennett means, I enjoyed listening to the interactions of my daughter (a TCK who grew up in Tunisia , Egypt and Lebanon , and has also spent significant time in Jordan , besides attending University in the U.S.

There are two possible phases of marginality, within Integration. At first, one might experience what he calls “encapsulated marginality,” “where the separation from culture is experienced as alienation,” and “constructive marginality,” “in which movements in and out of cultures are a necessary and positive part of one’s identity.” I have seen these two kinds of marginality with TCKs (third culture kids, i.e., people who grow up in a cultural setting that is different than their passport culture). For TCKs at the point of encapsulated marginality, the question, “where are you from?” may trigger an identity crisis – “I don’t know where I’m from; I don’t know who I am; I don’t know where I belong…” But for those who have developed to the point of constructive marginality, they may have come to have a positive sense of identity as a TCK – “I can go anywhere; I can adapt; I can fit in – I’m a TCK!”

|

| Can we integrate difference? |

Bennett concludes that “constructive marginality can be the most powerful position from which to exercise intercultural sensitivity,” and points out that “Cultural mediation could be accomplished best by someone who was not enmeshed in any reference group, yet who could construct each appropriate worldview as needed.”

Given the ever-“shrinking” world, with peoples traveling and migrating from and to just about everywhere, and given the levels of hostility and conflict (ethnic, national, religious, etc.) between different groups in the world today, there is a desperate need for people who have learned not only to adapt to cultural difference, but to internalize different cultural frames of reference and to live on the cultural margins. Such people can function as “bridge” people between different groups who are different, not just for mediating conflict (for which there is ample need), but also for mediating understanding and interaction.

The world needs more ethnorelative, interculturally sensitive peacemakers.

For more detail, see

Bennett, Milton J., “Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.” In Paige, R.M. (Ed). (1993) Education for the Intercultural Experience (2nd ed., p. 21-71). Yarmouth , ME

Bennett, Milton J., “Becoming Interculturally Competent.” In Wurzel, Jaime S., ed., Toward multiculturalism: A reader in multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 62-77). Newton , MA

Peace Quote of the Day - why won't Christians call Israel to account?

"So there are two strains within Christianity: one conservative (Christian Zionism) and one liberal/progressive (interfaith reconciliation). Both produce a tendency to support both the concept and the reality of the Jewish state. Both act powerfully to stifle criticism of Israel. This helps explain the reluctance - phobia might be a better word - of many Christians to call Israel to account for its human rights abuses and its denial of justice to Palestinians. We are presented with a daunting irony: Christians, attempting to atone for the crimes committed against the Jews, are by this very fact blocked from confronting the crimes committed by the Jews."

I think that there are more than these two strains within Christianity, and I believe the reasons for Christian support of Israel are more complex than he gets at here, but Braverman touches on a vitally important issue, which must be unraveled if we are to make any progress for peace in Palestine - Christian support for the State of Israel, and the fact that among what seems to be a majority of American Christians, it is impossible to voice any criticism of Israel, on any basis. Peace is not possible, without confronting and changing this roadblock.

Mark Braverman, Fatal Embrace

I think that there are more than these two strains within Christianity, and I believe the reasons for Christian support of Israel are more complex than he gets at here, but Braverman touches on a vitally important issue, which must be unraveled if we are to make any progress for peace in Palestine - Christian support for the State of Israel, and the fact that among what seems to be a majority of American Christians, it is impossible to voice any criticism of Israel, on any basis. Peace is not possible, without confronting and changing this roadblock.

Sunday, May 22, 2011

Beyond Ethnocentrism (2) – Pursuing Peace Through Growth in Intercultural Sensitivity: Adaptation

“One of the ways people inevitably increase their awareness when learning about other cultures is to move from thinking ‘My way is the only way’ toward thinking ‘There are many valid ways’ of interpreting and participating in life. And the process involves more than changing your thinking; it also involves adjusting your behaviors.”

Brooks Peterson, Cultural Intelligence (emphasis mine)

“The essence of ethnorelativism is respect for the integrity of cultures, including one’s own. In acceptance, the framework for appreciating cultural difference was established. At this stage, adaptation, skills for relating to and communicating with people of other cultures are enhanced.”

Milton Bennett, Towards Ethnorelativism (emphasis mine)

As we spend more time living and interacting with people in another cultural context, we may experience growth from Acceptance into Bennett’s next phase of intercultural sensitivity, Adaptation.

Acceptance (the previous phase) may have to do mainly with a change in perspective and attitude toward cultural difference (seeing it more positively, realizing it is there, being curious about and respectful toward difference), with an initial behavioral dimension of taking action to discover, understand, and learn about difference. It is possible to grow in accepting cultural difference, without living deeply or constantly in the midst of difference.

To grow into the phase of Adaptation, though, we need to be living in the context of cultural difference, and developing the skills for effective adjustment. This adjustment is comprehensive, involving cognitive, affective, and behavioral change over time. Cognitively, one begins to understand and see the world from the perspective of the people in the other culture. Behaviorally, one learns to adapt to do things in a way that is appropriate in the other setting. Affectively, one’s emotions are impacted over time, as feelings associated with the new worldview and cultural practices, and the value judgments associated with them, are internalized.

For example, through our years in Tunisia Tunisia

After living for years in Tunisia , and adapting to the Tunisian way of doing hospitality, we were often (emotionally) uncomfortable in hospitality situations in the U.S. U.S.

Note that adaptation, in Bennett’s model, is not assimilation. You don’t give up your culture, but experience an extension of your cultural repertoire.

“In adaptation, new skills appropriate to a different worldview are acquired in an additive process. Maintenance of one’s original worldview is encouraged, so the adaptations necessary for effective communication in other cultures extend, rather than replace, one’s native skills. The key to this additive principle is the assumption that culture is a process, not a thing. One does not have culture; one engages in it.”

One of the key skills in Adaptation is the ability to “look through the others’ eyes,” to construct reality that is nearer to their reality. Bennett contrasts this “empathy,” with the “sympathy” of ethnocentrism.

Can we adapt to the different other? |

“…I have contrasted empathy to ‘sympathy,’ where one attempts to understand another by imagining how one would feel in another’s position. Sympathy is ethnocentric in that its practice demands only a shift in assumed circumstance (position), not a shift in the frame of reference one brings to that circumstance; it is based on an assumption of similarity, implying other people will feel similar to one in similar circumstances. Empathy, by contrast, describes an attempt to understand by imagining or comprehending the other’s perspective. Empathy is ethnorelative in that it demands a shift in frame of reference; it is based on an assumption of difference, and implies respect for that difference and a readiness to give up temporarily one’s own worldview in order to imaginatively participate in the other’s.”

Adaptation takes time. And it changes us. As we live in another cultural setting, and adapt to the behavior, worldview, and even the value judgments and emotions accompanying sociocultural experience, we change. Even though this is not a process of assimilation, of exchanging our culture for the other, we become different people through the process. One author has called such people, “150% people.” And Bennett talks of becoming “marginal,” in the sense of becoming a person who is not straightforwardly “at home” in any cultural setting. When I returned to Minnesota after years in Tunisia (which used to be “home” but now no longer seems to be – for us know, “home” is wherever we are living), I could recognize my native culture, but I felt as if I was seeing it through different eyes. And indeed, I was. I had not become Tunisian, but I was no longer Minnesotan in the way I had been.

Would the cause of peace in the world be furthered, if more people entered into the world of different others, learning to deeply empathize, learning to see as they see, learning to understand how their behavior makes sense in its context, experiencing the fullness and richness of their life in all its dimensions? It seems that it would at least be a step in the right direction…

For more detail, see

Bennett, Milton J., “Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.” In Paige, R.M. (Ed). (1993) Education for the Intercultural Experience (2nd ed., p. 21-71). Yarmouth , ME

Bennett, Milton J., “Becoming Interculturally Competent.” In Wurzel, Jaime S., ed., Toward multiculturalism: A reader in multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 62-77). Newton , MA

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)